To examine the dynamics of art fairs, we’re taking a closer look at last year’s Miami Art Week. In line: Satellite Art Fair. With less than two months left until its next edition, the 10th edition of Satellite took place between December 4–8, 2024, across two venues. The program featured experiential content such as installations, performances, VR/interactive works, and workshops. Alongside traditional booth presentations, the fair emphasized night events, public–engagement works, and a curatorial approach that turned the fairgrounds into a space fluidly shifting between ‘work’ and ‘play’. By going beyond the classic booth layout and using open–air areas effectively through chamber–like installations, it offered both visual and intellectual satisfaction.

Multi–venue events, however, come with disadvantages; it’s challenging to coordinate audiences to visit both or multiple sites. Viewers with short attention spans often visit only one location [especially in touristic cities like Miami], get caught up in nearby attractions, go out to eat, miss event hours, and end up elsewhere in the city. For those who remained organized and focused, Satellite offered a complementary experience. First and foremost, its artist–to–artist, initiative–like structure, far from corporatized fair habits, filtered out visitors seeking visibility or social status–driven collectors. In their place stood visual representations of ideas like “enjoy the art itself”, “we do this because we love it,” and “presentation should not overshadow the work”. As a conceptual/experimental artist, I walked around with pride.

In my articles and interviews, I often emphasize labels; essential for preventing meaning shifts and balancing the experience for viewers from diverse socio–cultural backgrounds. Gallery labels usually include only Artwork > Artist > Medium > Dimensions > Price. In contrast, museum–style labels often add contextual information about the artist and conceptual hints about the work’s meaning. Since no gallery–like institutions mediated the process, the fair offered a great opportunity to observe how artists design direct communication with the audience. Some artists hung written messages describing their intended dialogue, some kept short captions, and others used handwritten notes on walls. It’s hard not to find the pencil–on–wall label both efficient and sincere. I’d love to see galleries adopt it where the concept fits. Beyond its setup ease and flexibility, it undeniably creates a more human connection during the viewing experience.

On several walls, I saw works by different artists hung so densely that there was almost no negative space; this somewhat undermined the fair’s otherwise mind–expanding atmosphere. After passing through the central area featuring large sculptures and installations, you enter an exhibition space designed like a maze of small chambers.

Entering the socio–political section, the audience was greeted by Eva Mueller’s Wall of Emotions [4:37]. Her practice explores LGBTQ+ and gender–centered themes. During the U.S. election results, Mueller began photographing her friends, pairing their portraits with words expressing their fears and expectations about how their lives might change; then printing and altering these images. Some of her other works can be difficult to watch, but that’s a reminder that not every artwork is for everyone, nor should it be.

Olivia Gossett Cooper! Amid the familiar demand for colorful, wall–friendly works, her practice was a conceptual oasis [16:21]. During Art Week, I toured eleven fairs and saw thousands of works. Hers were among the few that made me think, “Yes, this is exactly how conceptual content should be treated and shared”. Her visual language is both controlled and effortless; you find yourself searching for the uncontrolled side within that balance. The manipulation of ready–made objects, the diversity in her paper works, and the video presentation were all highly accomplished.

Moving on to the second venue; larger, with direct access from a busy street. Its glass façade made it more noticeable, and the entrance sculptures and window decals served as effective visual anchors. However, the number of staff on–site was below expectations; the fair itself, in addition to individual booths, seemed partly entrusted to the artists.

Music. DJs. While music can create a lively, social atmosphere at fairs and art events, I’m among those who believe it shouldn’t mix with visual art exhibitions. Fairs, shows [and openings], and workshops already subject you to a sensory overload that unconsciously weakens critical thinking about the works. That’s why online exhibition videos often seem more engaging when set to music, yet your experience with ambient or ASMR–style sound is far stronger and more meaningful. Please also recognize how rhythm speeds up the time you spend around an artwork. Instead of that, focus timelessly; free from distractions. Moreover, music interferes with the audibility of sound–based artworks; nothing worsens the viewing experience more than overlapping audio sources. With hundreds of works across themes [from joyful to critical, playful to political] music only enhances the ‘fun’ pieces while intruding on others’ conceptual space.

Now, to Melissa Haims’ Sleeping Under the Weight [25:04]. Created in memory of children who died from gun injuries, the work includes papers and clothing inscribed with the names of hundreds of children who passed away between January and December 2024. The hanging list extends from ceiling to floor, spilling onto the ground. At the center lies a bed covered in garments, complemented by clothes hanging on the wall. To avoid contextual confusion, let’s note that this work directly addresses America’s ongoing debate on gun ownership. U.S. artists sometimes assume that general global audiences share detailed knowledge of American politics or pop culture, but for European or Asian viewers, such works can leave interpretive gaps.

Inside pink televisions, we see the reflected faces of viewers captured by cameras [26:17]. Fabiola Larios’ Surveillance Cutie disguises surveillance under a cute, sparkling aesthetic. Featuring bedazzled vintage TVs and security cameras, a child mannequin in a pink dress, reflective Mylar surfaces, and a heart–patterned rug, the installation creates an atmosphere that is simultaneously adorable and unsettling. By merging hyper–feminine imagery and nostalgic technology, the artist hides the discomfort of constant surveillance beneath the veneer of innocence. Viewers, both reflected and recorded, become part of the experience; prompted to question how sweetness and beauty can serve as tools of control. At its core, the work comments on privacy, vulnerability, and the performative nature of identity in the digital age. In a time when people ignore surveillance cameras yet obsess over recording themselves with more visible ones, it’s a striking piece. The debate over consent has, after all, brought even street photography to the brink of extinction.

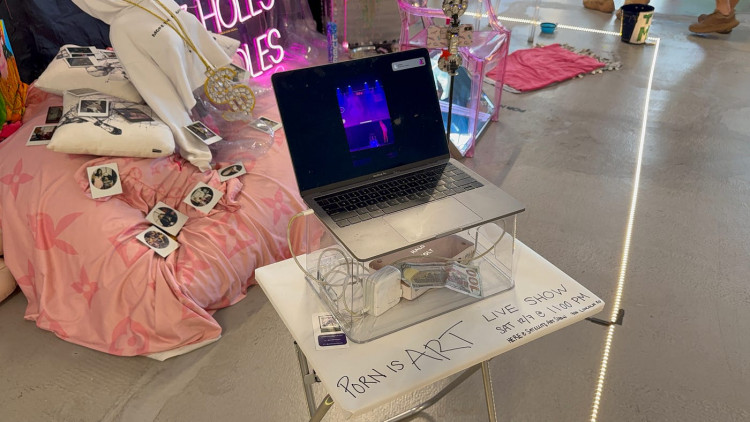

With Objectify Me, Nikki Sweet [26:34] blurs the thick line between pornography and art. The subject is particularly provocative at a time when OnlyFans culture is being defended as providing women with economic ‘freedom’. Without fixating on objectification, Sweet freely presents her performances, complete with a price list of videos and images, displayed on a banner within her booth. Polaroids, a laptop, a desk lamp, a TV; rather than a single unified piece, it’s an exhibition of ongoing, documented performances.

Returning to the theme of objectification, one must remember: a person is the sole authority over their body. When beauty and desire turn it into a consumable object [regardless of gender] the individual unconsciously sits a beauty–meaning scale. Consequently, their identity and intellect [if presented as the key identity] are overshadowed. The same problem applies to art: aesthetically pleasing, decorative works are easily bought, sold, and adaptable to any space, while works bearing conceptual or existential weight are dismissed as ‘depressing, non–decorative, reminders of pessimistic realities’. Thus, in a market where beautiful bodies are manufactured for desire, creating them in a consumable format only perpetuates the historical mistake of ‘secondary treatment’ that many societies have long struggled against; placing yet another barrier before achieving true gender equality.

Miami Art Week Fairs: Satellite

Yorumlar (0)

Bu gönderi için henüz bir yorum yapılmamış.

Yorum Bırakın